Mr Yum

Disruptive Hospitality Technology

Mr Yum is a QR code based digital menu and ordering platform for the hospitality industry. Using a QR code allows customers to quickly pull up a restaurant’s digital menu using their mobile phone camera and order without downloading an app. Mr Yum also integrates with other restaurant systems, such as POS, improving staff productivity and customer interaction.

Its unique approach was an early bet on the QR code. Additionally, it was initially designed as an in-venue solution with a clear focus on making the numbers work for the restaurant side of the platform. Restaurant and hospitality customers are seeing a 20-40% increase in average order values and an increase in staff productivity.

The business was founded in late 2018 by Kim Teo, Adrian Osman and Kerry Osborn, with CTO Andrei Miulescu joining in June 2019. Kim, Kerry and Adrian had worked together years before founding Mr Yum in a previous startup where they learned the importance of making the economics work for the platform’s supply side. This level of empathy is reflected in their aim to provide hospitality businesses with a strong ROI.

COVID accelerated its adoption to over 10 million customers due to:

Mass market adoption of the QR code for contact tracing, contactless payments and ordering.

The increased share of orders of the delivery apps which has accelerated the maturity of this industry. This gives disruptive providers like Mr Yum an opportunity to benefit from the unbundling of the e-commerce and marketing components for which delivery apps are charging restaurants a 30% fee.

Their $11 million capital raise gives them the resources to expand into the US and UK at a critical time. This capital will go a long way if the experience in Australia is repeated.

The Magic of Hospitality

There is a certain romance and passion in running a hospitality business. Whether it is a genuine love of food or the satisfaction of seeing happy customers from a great service, this passion drives the people involved through the operational complexity the industry is known for. To give me a sense of this, I included feedback from the people who are key to this incredible industry.

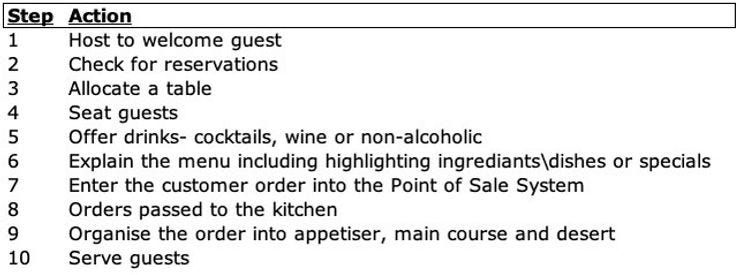

Remember your last great experience at a restaurant? On an evening out, I spoke to Laurent Tapullima, pictured above, to get a sense of the steps involved.

These steps were on display when I took Mum out on a well-deserved lunch date to Mr Miyagi, a popular Japanese restaurant in Windsor, Melbourne. We were served by Bella, who patiently explained the menu and helped us choose our dishes. Mr Miyagi is also an early Mr Yum customer. I had the opportunity to speak to Lachie Topp, the Assistant Venue Manager, who gave me some insights on Mr Yum, which I will come back to later.

I sensed a genuine passion from Laurent, Bella and Lachie to serve and build connections with customers even during a busy lunch or dinner service, and I am grateful for the insights they gave me.

However, I also felt there was scope for technology to streamline restaurant operations and allow staff to focus on their real passion - interacting with customers.

Technology Adoption and the Rise of the Delivery Apps

Restaurants have lagged in terms of technology adoption. Investing in technology can be expensive, and restaurants are known for tight margins. Below is a break-down of Chipotle’s financials as an example:

The most obvious recent innovation is the incorporation of delivery. While the first recorded pizza delivery took place in Italy in 1889, the take-up of delivery has been slow. As an example, Deliveroo’s recent IPO prospectus stated that over 90% of the restaurants on their platform did not previously offer delivery.

The twin innovations of the smartphone and flexible employment resulted in the rise of food delivery platforms such as Uber Eats, Door Dash and Deliveroo.

Fueled by investment capital, this market has grown rapidly. In the US, food delivery app revenues have grown at 25% per year to $26.5 billion in 2020.

In 2018, UBS and Frost and Sullivan estimated this segment to grow at 14-20% per year.

This rapid take-up speaks to the value these delivery apps have provided to consumers. If you’ve ever used these apps, it’s hard to argue with the convenience and discoverability they bring. However, this has come at a cost in the form of high commissions.

Growing the Pie?

Platforms like Uber Eats charge restaurants a 30% commission on orders delivered through their platform. DoorDash’s IPO prospectus filing gives an indication of how this fee is split between restaurants and the consumer:

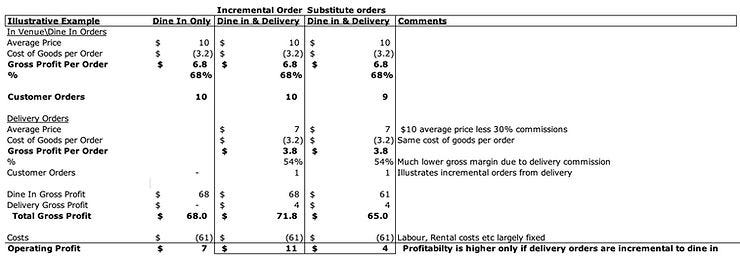

In the above example, the restaurants will be giving the app platforms roughly 30% of the total order cost. However, as previously discussed, restaurants are low-margin businesses. As such, when can it make sense for them to pay the high commissions that these platforms charge?

The answer is when these platforms bring incremental orders to the restaurants. This is because of the high level of fixed costs such as rent in restaurants that do not change with customer orders. I have used the numbers in the Chipotle example to illustrate this below:

The above illustration shows how the restaurant will benefit from an additional delivery order (i.e. growing the pie). The reverse is true if the delivery app causes consumers to substitute away from dine in orders to lower margin delivery.

An Accenture report found that the app delivery platforms contributed $2.6 billion out of the $47 billion Australian restaurant revenue in 2019. 70% of this amount was incremental to what restaurants would have earned without the delivery apps, i.e. delivery apps were growing the pie.

This would explain the rapid take-up of these app platforms. Spending on these apps was only $400 million in 2016 compared to $2.6 billion recorded in 2019.

Disruption - The Case for Unbundling

Restaurants are a mature industry, growing at low single-digit rates pre-COVID. Incremental orders become harder to achieve as these delivery apps become a more significant part of the industry’s (and individual restaurant’s) sales. At that point, they will increase competition amongst restaurants rather than bringing in more orders. This will make their high commissions harder to justify.

This dynamic was brought to the fore during COVID. Government-mandated shut-downs saw restaurant sales fall 23% in March 2020, and delivery became a much larger proportion of sales. This led to calls for the delivery apps to reduce commissions, with some states in the US legislating fee caps of circa 15%.

To be fair, it is hard to accuse the delivery apps of deliberately overcharging their restaurant customers, given their own issues with profitability.

The delivery apps can be thought of as 2 products grouped into 1 bundle. They are:

E-commerce – Where customers can order, pay and have online orders delivered by a delivery network of drivers who transport the food in a timely manner

Marketing – The delivery app acquires customers and allows them to discover the restaurant on their platform

They provide a very convenient service for consumers, and I found the restaurant service levels excellent while posing as a potential restaurant partner with DoorDash. However, offering all these products makes the bundle expensive and more open to disruption via unbundling.

Unbundling is a typical form of disruption in a maturing industry where the requirements for the various components are understood well enough for specialist providers to provide a more appealing (or affordable) service to over-served customers.

A well-known example of this is the cable TV bundle, which broadly consists of sports and entertainment channels. For years, cable companies have used sports as a customer acquisition tool. They subsidised these sports channels by adding (and charging for) ever more entertainment channels. Between 1995-2005, the number of channels in the average cable bundle size doubled as cable bills rose 3x faster than inflation.

This model has come under increasing pressure as streaming services like Netflix put out cheaper entertainment content for non-sports fans. Cable companies are now reluctantly unbundling.

In the case of the delivery apps, I suspect that the marketing component is subsidising the delivery component. It is expensive to incentivise a network of delivery drivers to deliver food in a timely manner, e.g. while still warm.

The delivery apps have driven the adoption of technology by restaurants but the stage is now set for disruptors like Mr Yum.

The Journey to Mr Yum

Mr Yum was founded by Kim Teo, Adrian Osman and Kerry Osborn in late 2018. CTO Andrei Miulescu joined them in June 2019.

Kim, Adrian and Kerry have had a history of working together before Mr Yum. Kim and Kerry were co-founders in a previous venture called Neighbour Flavour in 2015. This was a marketplace to buy home-cooked food from people who lived nearby.

Neighbour Flavour was itself being incubated in Pitch Blak, a startup education and advisory business where Adrian Osman is a co-founder.

Kim has been very open in discussing the challenges Neighbour Flavour faced. Specifically, she discussed the importance of having a clear focus on unit economics and success metrics. I believe it also gave them a sense of empathy with the supply side of the platform.

In this case, it was the cooks producing the home-cooked meals. Kim and Kerry realised that these cooks were not making sufficient margin and were not cooking or using the platform frequently. Kim and Kerry returned the $500,000 they raised. They then both did stints at Pitch Blak as Head of Ventures and Head of Growth, respectively.

Mr Yum – A New Way to Order

The idea for Mr Yum came about when the founders realised that rather than showcasing the food, menus looked like text-based documents which haven’t evolved for centuries. Have you ever looked on Google or Instagram to figure out what an item on a menu would look like?

Mr Yum, therefore, started as a digital menu, with quality photographs showcasing the food. They then added other features which helped the restaurants serve their customers and grow their business. Examples include batching orders by a group of friends into a single docket and marketing tools.

Another important early feature was the use of QR code as a means for the customer to bring up the digital menu. The QR code was originally designed as an evolution of the bar code in Japan in the 1990s. Information is stored as a series of pixels in a square-shaped grid. When scanned, the QR code allows the user to quickly access information such as a website (QR stands for Quick Access). This allows the diner to access the menu by scanning the code with the native camera app on her or his smartphone, i.e. no need to download another app. The founders took a bet on this technology as Apple had just started to roll out this feature in their smartphones.

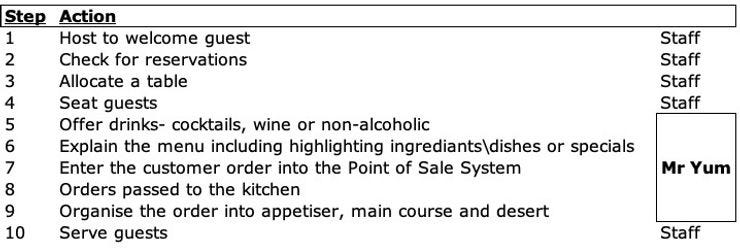

Combining a digital menu and integration with the restaurant’s back-office systems reduce administrative functions like taking orders or communicating with the kitchen, as shown below. This allows staff to be more productive and serve more customers.

Mr Yum also helps with upselling, with restaurants reporting a 20-40% increase in average order value. Below is an example of my meal at Vapiano, an Italian restaurant in Melbourne. Note how the ingredients are described, with additional options clearly laid out.

Importantly, unlike the delivery apps, Mr Yum started as an in-venue application with a strong focus on the restaurants. The founders have built a simple product with a strong return on investment for the restaurants (pricing is circa 5%). It is reminiscent of their experience with Neighbour Flavour, where they learnt the importance of making the numbers work for the supply side.

Both Mr Miyagi and Vapiano staff had positive feedback regarding Mr Yum’s ease of use and ability to take more orders from customers, particularly during peak times.

As a result, Mr Yum achieved strong early traction, particularly after The Australian Venue Co became an early customer (and later investor). Within 6 months, Mr Yum was attracting 20,000 users a month. They raised $1.5 million in May 2019, more than double the $700,000 they initially sought.

COVID – More Important Than Ever

COVID has caused an enduring lift in the adoption of Mr Yum on 2 fronts

The ability to do away with paper menus and contactless ordering has caused ‘mass-market adoption’ of QR codes among customers and businesses. The productivity benefits they have experienced will likely cause them to keep using QR code ordering post-pandemic. This is a view shared by The Restaurant and Catering Industry Association.

The sharp increase in delivery brought home how expensive the delivery apps are, as previously discussed. Mr Yum pivoted quickly to enable delivery by partnering with delivery networks or allowing the restaurants to deliver themselves. Restaurants now have the option to purchase these services individually without the marketing component, which the delivery apps charge a high price for.

As such, the traction achieved has been breathtaking. The number of venues using Mr Yum grew 950% since March 2020, and Mr Yum served 10x more customers in January 2021 compared to the prior year. Importantly, Mr Yum’s growth post-reopening (October 2020 to January 2021) has remained strong at 46% month on month.

The delivery apps are trying to adjust. For example, Uber Eats has reduced its delivery fee to 30% and is introducing a dine-in digital menu option for a 3% fee. However, I believe it will be difficult for Uber Eats to move away from the more lucrative full-priced delivery bundle.

As such, it will be difficult to match Mr Yum’s focus and speed in its digital menu and ordering. Examples of Mr Yum’s continued innovation include acquiring Venue Safe, a contact tracing app, to incorporate into the Mr Yum platform and allowing customers to set up digital tabs at a restaurant.

The recent $11 million funding round provides capital for additional product development and international expansion in the US and UK. The US and UK are 6-9 months behind Australia in terms of reopening, which presents a unique window of opportunity to drive the adoption of the platform.

The round was led by TEN13 (a syndicated platform linked to Shark Tank panellist Steve Baxter’s family office) and included Air Tree Ventures as a major investor. Other investors include Tractor Ventures CEO Matt Allen, UNIFIED Music Group as well as Linktree founders Alex Zaccaria, Anthony Zaccaria and Nick Humphreys.

There is a strong level of operational expertise that they can benefit from in the above investor base. In particular, there are many similarities with Linktree's rapid adoption, which I previously profiled. Mr Yum has the same ingredients of a simple product, with a strong restaurant ROI causing restaurants to share their experience and is riding the powerful trends of QR code ordering and delivery app unbundling. If so, their progress so far is only the beginning.